Broadband Access and Digital Inclusion in the United States

Over a relatively short period of time, availability of the Internet and the meaningful usage of online services and applications has become a necessity for functioning in modern society. For billions of people worldwide, the Internet is an essential tool for learning, doing their jobs, and connecting with one another. This important resource facilitates creativity and exponential change in our society, as users are able to create new products and services that continue to transform life in the twenty-first century. Yet, in many areas in the United States, a lack of affordable Internet access or digital skills excludes many from the opportunities that high-speed Internet offers. As reported by the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC), one in ten Americans does not have access to high-speed Internet. Further, 39 percent of rural U.S. residents lack high-speed Internet access.

As our society increasingly relies on the Internet for work, education, commerce, and leisure, lack of access becomes increasingly detrimental to those affected. In 1999, 32 percent of Fortune 500 firms recruited employees online. By 2007, 100 percent of Fortune 500 firms recruited employees online. While a job seeker in 2007 still had the option to apply for positions with Fortune 500 firms via mailed paper applications, by 2012, almost all Fortune 500 firms posted jobs and accepted applications exclusively online. In the span of five years, use of the Internet to apply for these jobs transitioned from an option to a requirement. Inability to apply for jobs online is just one example of the many disadvantages caused by gaps in digital access.

Realizing the importance of this issue, stakeholders at all levels of government and across sectors have been actively seeking solutions to achieve greater broadband Internet access and digital equity.

What Is “Broadband” Internet?

The term “broadband” is generally used to refer to high-speed Internet service. A number of technologies can be used to deliver broadband Internet service. These include:

- Wireline Technologies

- Fiber to the Premise (FTTP) is the “gold standard” in broadband technology. FTTP is the most expensive to deploy, but can deliver consistently high speeds reaching 1 gigabit per second (1 Gbps = 1,000 megabits per second [Mbps]) and higher.

- Cable Modem uses a coaxial cable connection to deliver broadband with download speeds historically ranging from 6 Mbps to more than 100 Mbps. The DOCSIS 3.1 standard allows speeds over 1 Gbps. Bandwidth is managed through shared connections.

- Digital Subscriber Line (DSL) uses copper telephone lines to deliver broadband with download speeds generally under 10 Mbps. Aging networks can degrade service over time, which can decrease speeds delivered to the home.

- Broadband over Power Lines (BPL) uses existing electric wiring along with fiber to deliver broadband through electric outlets. BPL requires special equipment installed at the home. This technology has seen limited deployments.

- Wireless Technologies

- Fixed Wireless uses a combination of a fiber backbone and wireless towers to deliver broadband at speeds comparable to DSL. This technology can be quickly deployed at lower costs with a wide reach, but many plans have data usage caps. Different standards of fixed wireless exist (e.g., Worldwide Interoperability for Microwave Access [WiMAX], Long Term Evolution [LTE]).

- Mobile Broadband is a combination of cellular and data service generally for use on mobile devices. It typically complements wireline connections, but some companies provide home broadband service delivered over mobile broadband networks. Many plans have caps that limit usage.

- White Space is a new and emerging technology that uses the empty fragments of television spectrum scattered among frequencies. This technology is less expensive to deploy in areas without much existing infrastructure, and can broadcast a signal that travels through physical obstacles, such as trees and mountains, without diminishing, due to the usage of lower-frequency bands that allow signals to propagate farther. The FCC requires networks to follow strict requirements not to interfere with existing broadcasts. A number of trials have been underway both domestically and globally.

- Satellite is a two-way transmission of Internet data passed between satellite and a dish placed at the home. Because data traverse long distances, latency delays can occur. Most plans have data caps.1

As advances in technology continue to change the way that we live, work, and play, the accepted standard for Internet speed has changed over time. In 2015, the FCC updated its definition of broadband to represent a minimum speed threshold of 25 Mbps download and 3 Mbps upload. The previous standard for high-speed Internet was 4 Mbps download and 1 Mbps upload. To put these speed thresholds in a practical context, at 4 Mbps, it would take an estimated 2 hours and 46 minutes to download a two-hour video, while at 25 Mbps, the same video could be downloaded in an estimated 26 minutes.2

The change in the definition of broadband reflects the fact that Americans’ use of data-hungry applications such as streaming video has grown and that households often connect multiple devices simultaneously to the Internet. The FCC’s previous standard included Internet plans that would not allow people to use many modern applications or multiple devices at the same time.

Broadband Adoption and Digital Inclusion in the United States

While access to reliable, high-speed Internet is a requirement for closing gaps in access, adoption is another important element. In many communities, rates of adoption are lower among certain segments of the population even though Internet access is available. According to research conducted by the Pew Research Center, Internet use in the United States is significantly lower among individuals aged 65 and over, lower-income individuals, and individuals identifying as Black or Hispanic. The reasons for these differences vary, but advocates of digital inclusion frequently cite the cost of service, access to devices, and lack of digital skills as common barriers impacting these groups.

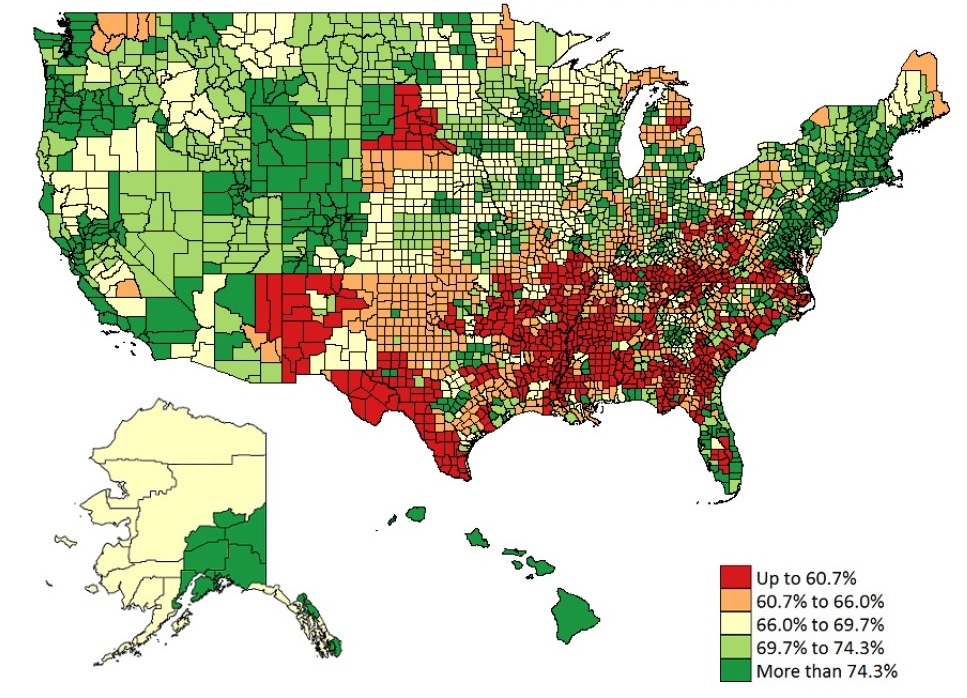

Unlike residents in geographically smaller nations, a large proportion of Americans live in sparsely populated areas. Rural communities in the United States are more likely to be underserved by private Internet service providers (ISPs). These companies prefer to spread construction costs over as many users as possible, as this lowers the cost per user and results in increased profit. Consequently, ISPs find it challenging to build networks in sparsely populated areas of the United States, leaving many rural residents to rely upon slow, dial-up service or very expensive satellite service. In less densely populated places, many residents lack access to high-speed Internet, or do not subscribe to the Internet due to low quality of service, unaffordable rates, or other drivers of low adoption (e.g., poor digital literacy, lack of perceived relevance).

According to the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project from 2013, 19 percent of survey respondents said they did not use the Internet due to price. Thirteen percent did not have a computer (likely because they could not afford one); another 6 percent said the Internet service itself was too expensive.3

According to the 2013 American Community Survey, computer ownership and Internet use are most common in homes with householders who fall into one or more of the following categories—younger, Asian, white, high income, urban, or highly educated.4 Patterns for individuals were similar. A report released by NTIA found the same trends to hold true in 2015.5

The Pew Research Center concentrates on the non-Internet-using peers of the people described above—15 percent of U.S. residents. In the United States, men and women are just as likely to not use the Internet; in contrast, women in many other countries are more likely than men to be offline. Blacks and Latinos are far less likely to use the Internet than Whites and Asians. Other people with a high likelihood of being offline are the elderly, people with annual household income less than $30,000, people with a high school diploma or less, and rural residents. The following chart from Pew provides insight into offline U.S. residents.

The Pew Research Center concentrates on the non-Internet-using peers of the people described above—15 percent of U.S. residents. In the United States, men and women are just as likely to not use the Internet; in contrast, women in many other countries are more likely than men to be offline. Blacks and Latinos are far less likely to use the Internet than Whites and Asians. Other people with a high likelihood of being offline are the elderly, people with annual household income less than $30,000, people with a high school diploma or less, and rural residents. The following chart from Pew provides insight into offline U.S. residents.

Recently, Pew published research about Americans’ digital skills and trust using online sources to pursue online learning. The key finding is that 52 percent of U.S. adults are hesitant to use online learning. As more educational resources move online, these individuals will be at a severe disadvantage.

The Impact of Expanding Broadband Access and Digital Inclusion

The benefits of enhancing broadband access in the United States are significant. One economic study estimated that as early as 2006, spending on broadband accounted for $28 billion in U.S. gross domestic product.6 Broadband Internet also facilitates innovation and creativity, which in turn drive additional economic growth and global competitiveness.

While the economic benefits are clear, there are also important social benefits created by inclusive broadband access. Broadband Internet opens the door to a world of resources for learners of all ages. From early childhood to adult education, access to broadband increases educational opportunities exponentially. As many U.S. communities have seen through the growth of local tech communities, broadband access can also empower new entrepreneurs and foster greater civic engagement.

Maintaining a focus on equity and inclusion will ensure that all members of society have access to the resources that broadband Internet offers. For many living in the United States, these efforts will translate directly to improved economic mobility and enhanced quality of life.

Local Government’s Role

In the movement to expand reliable high-speed Internet access to all, local governments have an important role to play. This role can include assessing and addressing the unique needs of their communities, providing network access where the private market does not, convening public and private stakeholders to create or expand networks, and removing barriers to access by offering subsidies and digital literacy training.

Local governments can also pursue legislative and policy solutions to improve the availability of high-speed Internet in communities. These will include overcoming barriers such as:

- Hostile legal and political environment toward government involvement in broadband markets

- Internet service provider monopoly and duopoly leading to minimal competition in many communities

- High cost of building a fiber network.

Action by local governments could seed and nurture the infrastructure necessary for broadband access and incentivize improvement in digital literacy locally, regionally, and nationally. Given the rapid pace of technological advancement and the impact of broadband on U.S. communities, it will be increasingly important for local governments to take a leadership role in moving their communities toward greater access and inclusion.

1. “What Is Broadband?” New York State Broadband Program Office, accessed October 27, 2016, ↩

2. Community-Based Broadband Solutions: The Benefits of Competition and Choice for Community Development and Highspeed Internet Access, Executive Office of the President, January 2015, ↩

3. “Who’s Not Online and Why,” Kathryn Zickuhr, Pew Research Center, September 25, 2013, ↩

4. Computer and Internet Use in the United States: 2013, Thom File and Camille Ryan, November 2014, ACS-28, ↩

5. “The State of the Urban/Rural Digital Divide,” Edward Carlson and Justin Goss, National Telecommunications and Information Administration, August 10, 2016, ↩

6. Community-Based Broadband Solutions: The Benefits of Competition and Choice for Community Development and Highspeed Internet Access, Executive Office of the President, January 2015, ↩